Growing a garden & growing a pair: On possibly leaving home

Growing up or growing apart? Family ties and the fear of moving out.

Words by Sammi Wu | Edited by Liên Ta

I WAS SNIFFLING by the time we left IKEA but I’m sure we could’ve kept going. We wanted to keep going — wanted to keep pulling each other’s hands through the showrooms, wanted to prod more couches and ponder curtains, wanted to slip into a future we didn’t yet have. It’s always hard to recall a story that happens so fast that every event bleeds into another. But falling in love was like that for me.

I thought, later, about how that’d probably been the start of it. I’d never seriously considered the prospect of leaving home until I met my boyfriend; consequently I’d never been confronted by the thought of how much it could hurt to leave, whether that be for love or otherwise. And love would be a good reason, but good reasons can still be painful to bear.

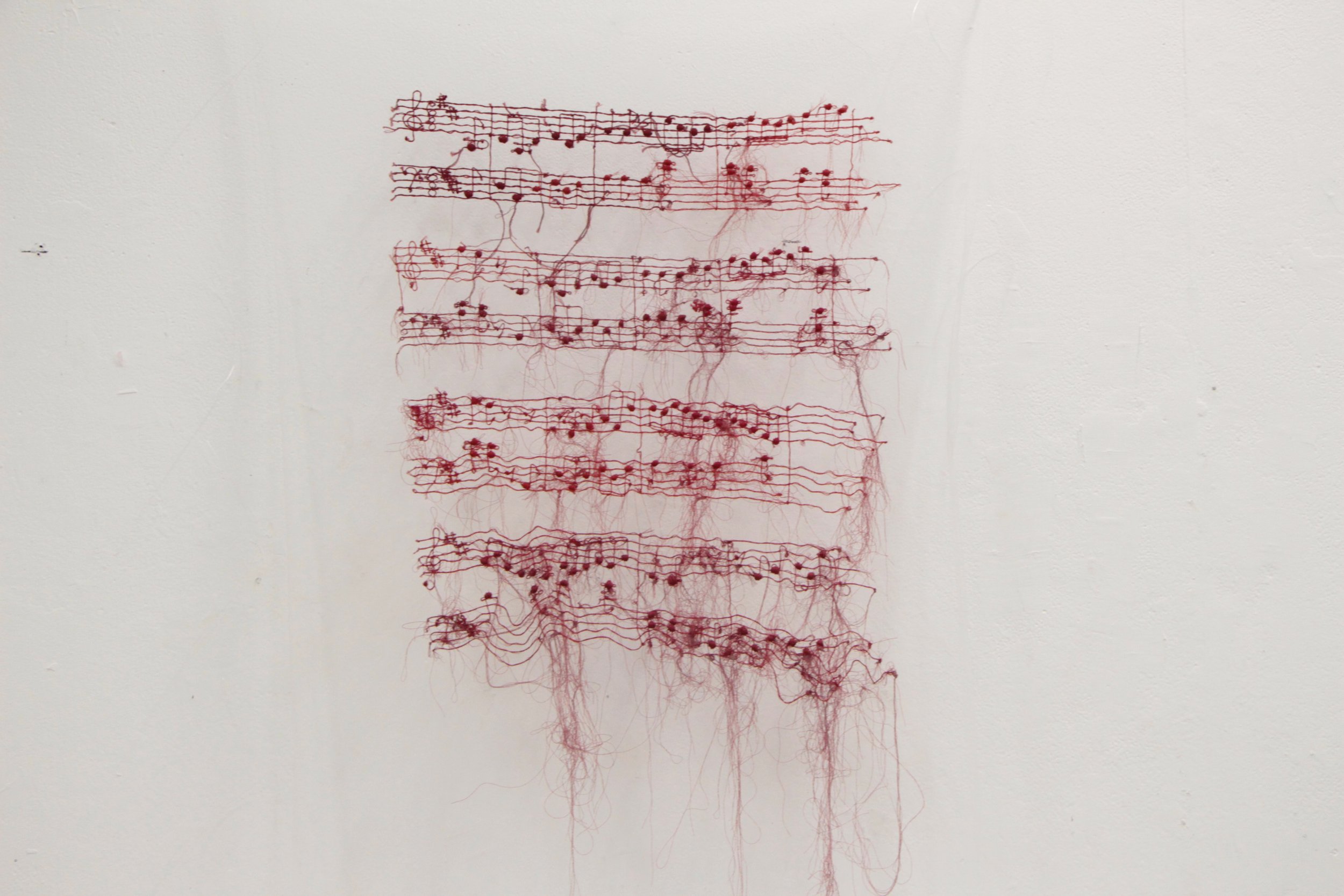

Emily Song

(a remembering of) Piano sonata no.18 in D major, k.576 I. Allegro, 2023–ongoing, embroidery on tulle

Like many eighteen, nineteen, twenty-somethings, I’d spent the blur of time after high school hurtling into the unknown, at an acceleration wholly against my will. I was the eldest child, and there was suddenly no hand-holding from my māma and bàba, who thrust me the reins at the earliest opportunity. This was no five seater sedan — this was a wild thing; a horse. I was trying to find my footing and this beautiful bastard of a mare was hellbent on me losing it. We were careening into the sun and there were no brakes. There wasn’t even a backseat driver — again, this was a horse. There was only the scrambling, only a desperate clinging onto of routines, routes, and customs I’d memorised over a lifetime spent navigating (and mastering) childhood under my parents’ direction. At the time I’d hated the suffocation: I’d always made sure to stay in the perilous in-between of what they wanted and what I did, not always the good daughter but never too bad. Now with total freedom, I knew there could be nothing worse for a child who’d been raised under restraint.

In struggling to come to terms with the devastation and subsequent transformation of my world, I felt myself rapidly losing my marbles. I remember this ache in my chest on orientation day that had me legging it to the bus stop before noon, punctuated by the frantic, metronomic click-clack of my shoes, much too fast for someone who had nowhere to particularly be except the very place I was running from. Still, I wanted to go home. I remember pressing my forehead against the panelling of the bus, distressed by the unfamiliar stop names and my favourite song pitifully stuttering through the left earphone I couldn’t afford to replace, and the fact that the only person I’d talked to that morning had casually dropped, like an anvil on our conversation, Oh yeah, I finally moved out last month, actually — so my parents are alone now. I remember that the sheer significance of that statement, even if negligible to them themselves, had punched through me like a jagged breath. I’m not so stupid as to not know this reaction was likely misplaced, and I’m not so stupid as to assume that every other teenager-slash-young-adult in this world must have had the same complex, wretched, wonderful and all-consuming relationship with their adolescence that I did. But still, I was overcome with despair. And then I vowed to not think about it, and to not think about moving out, for, well, at the least, another two to three years — whereupon my younger sister would enter this terrible, unknown world with me, and maybe I could provide her the guidance that I myself had been lacking, and maybe we could think about it together.